Social Corporation for Community Advice and Training

For almost twenty years, the Social Corporation for Community Advice and Training (COSPACC) has been dedicated to the assistence, organisation and accompaniment of victims of human rights violations especially in the departments of Boyacá and Casanare, and the capital Bogota. All this, without losing sight of its main objective, which is the reconstruction of the social fabric and permanent training in the promotion of human rights and international humanitarian law (IHL). Together with allied organizations, COSPACC has been making public complaints and contributes to judicial cases before ordinary justice and transitional justice courts.

“As Casanare has been a highly victimized area, especially by multinationals dedicated to oil extraction, for a long time seeing a foreigner on the ground equalled seeing a threat. However, with PBI we have managed to build trust, achieve different organizational dynamics, walk on foot for long days to get to remote places where local communities were waiting for us. Today, we can say that Peace Brigades has been part of reconstructing the social fabric, of acting together, and also of learning by doing.”

Fabian Laverde, COSPACC President

History: twenty years rebuilding the regional social fabric

The history of COSPACC is closely linked to the violence of the 1990s in the department of Casanare, when systematic human rights violations committed by paramilitaries of the Casanare Farmers’ Self-Defence Forces in collaboration with the National Army’s 16th Brigade, based in the city of Yopal, wiped out a large part of the regional social movement. Research has shown that these crimes were partly funded by large landowners in the region interested in expanding their properties, as we as oil companies looking to protect their exploitation infrastructure.1

The dynamic led to the cruel murder of the majority of the members of the Casanare Farmers´ Departmental Association (ADUC), dedicated to defending the rights to land and decent housing. In 2002, some of the surviving members of the ADUC created the Social Corporation for Community Advice and Training, COSPACC. With a territorial focus on the foothills of the plains, the region located between the departments of Boyacá and Casanare, its founders were committed to addressing massive human rights violations and rebuilding the region’s social movement.2

From 2005, the violence began to decrease in Casanare, partly because some of the paramilitary groups in the region decided to demobilise under the provisions of the Justice and Peace Law.3 However, to this day, being a social leader in the department still carries serious risks. For COSPACC, the accusations, threats, attacks and even murders of its members have not stopped.4

The struggle for the defence of the territory

COSPACC carries out its activities mainly in the departments of Boyacá and Casanare, as well as in Tolima and Arauca, in areas severely affected by poverty and violence, human rights violations and environmental damages. These are often related to the activity of the extractive industries operating in these regions. The Corporation accompanies and gives advice on legal matters to persons and communities that fell victim to human rights violations during the armed conflict and after the signing of the Peace Agreement with the FARC (2016).

“Main issues that we are currently working on include the struggle for the defence of our territories and for the right to defend human rights, addressing the lack of guarantees protecting the work of defenders,” says Fabian Laverde, president of COSPACC. Recently, the organization has been creating and strengthening a regional human rights network. “Through the network in Boyacá and Casanare, we managed to establish direct support and training for women, peasants, indigenous people and also students.”5

Accompanying local communities in their organizational processes and solidarity activities is another of COSPACC’s strong points, as is the promotion of organic and sustainable agriculture. It does this not only to address the lack of food security in the regions, but also to promote small-scale rural projects as an alternative to the devastating impacts of the large extractive industry.

The reality of small victories against injustice: Martin Ayala

Shining a light on obscure relations of multinational oil companies

Together with allied organizations such as the Committee for Solidarity with Political Prisoners (CSPP– also accompanied by PBI), COSPACC investigates and documents cases of human rights violations and breaches of international humanitarian law (IHL). These include crimes against humanity, with a particular emphasis on extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances.

The organizations jointly publish public denunciations and file disciplinary and criminal complaints before the ordinary justice courts, and submit investigative reports on crimes committed during the decades of armed conflict in the country to the the transitional justice system. One of these reports covers cases of extrajudicial executions presumably committed under the command of the 16th Brigade in the department of Casanare.6

Another case investigated by COSPACC has to do with the activities of British Petroleum (BP) during its operations in the region in the 1990’s until their exit from Colombia in 2010. The alleged – direct or indirect – involvement of this multinational company in human rights violations committed by paramilitary groups in Casanare has drawn international attention. The murky relations of BP during the armed conflict included agreements signed with the Colombian Ministry of Defence, under which the National Police and the National Army provided special services to the company to protect its oil infrastructure.7

During a congressional debate on the extractives sector’s security policy in 2015, senator Ivan Cepeda Castro publicly denounced that the agreements signed by mining and hydro-electric companies involved Army battalions presumably responsible for the highest numbers of extrajudicial killings.8

Women as protagonists of transformation

In Casanare, the region where COSPACC carries out most of its work, the Corporation supports organizational processes and supports actions in defence of the human rights of peasants’, women’s, student and youth organizations.

In this context Fabian Laverde highlights the support for the Association of Women United for Casanare (ASMUC): “At COSPACC we see women as active promoters of transformation. Women had to assume protagonist roles during the conflict and this is visible today in the settlements where displaced families and families affected by violence are living. Most of these settlements are made up of female heads of households. Inspired by our vision of women as leaders of change, we have actively contributed to the founding of ASMUC.”9

This organization works for decent housing and other rights of the displaced communities that inhabit the settlements, which are characterized by critical humanitarian conditions.10

“We have to keep our wits about us and defend health, education and life”: Ninfa Cruz

Defending social protest in the regions

In recent years there has been a marked increase in the use of criminal law to obstruct the work of human rights defenders and social leaders in Colombia. According to a 2019 report by the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT), the misuse of legal institutions in order to silence the defence of human rights and social protest constitutes a deliberate policy in the country.11

This practice is also evident in the regions where COSPACC works. “We permanently accompany social mobilisation in the territories and actively promote social protest with our local allies,” says Fabian Laverde. “Despite the recent persecution and prosecution of more than ten social leaders in Casanare, the response was more mobilisation, and more social sectors joined. COSPACC has been working to achieve this for fifteen years and today we see that people have left their fears behind. They’ve finally started to recognise and support their social leaders.”12

The Corporation is now also recognized by local authorities, who open their doors to conversations, which did not happen before. However, the fear of being captured always remains latent, according to Laverde. This risk, together with the current government’s stance on the large number of attacks and murders of social leaders and defenders in Casanare and other regions, seriously hinders the work of human rights defenders. “The Government publicly defends three very distorted arguments to explain reality: drug trafficking, illegal economies and criminal gangs, but for us not everything is related to this. As long as the Government does not recognise the systematic nature of the killings and continues to treat these as isolated events, this will remain an incentive for the murderers.”13

In September 2019, COSPACC and CSPP brought the case file of eight environmental and community leaders from Casanare to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva (Switzerland). The eight leaders, from the municipality of San Luis de Palenque, were captured in their homes in a major police and army operation in November 2018. According to the Prosecutor’s Office, their arrest occurred on suspicion of being part of an organized crime group that used social protest as a “façade” to obstruct the activities of hydrocarbon companies in the region, among them Frontera Energy – formerly Pacific Energy. In reality, according to COSPACC and CSPP, the leaders were “deprived of their liberty solely for participating in social organizations, holding meetings and promoting peaceful mobilizations” against the multinational.14

In the report “Criminalization of the defence of human rights in Colombia: the judicialization of land, territory, environment and peace defenders” (2019), the two organizations document this and other cases of local leaders who have fallen victim to the misuse of the judicial system to impede their work in 14 departments of the country.15

Uncovering the enforced disappearances in Casanare and Boyacá

As part of its efforts to support the work of the Integral System of Truth, Justice, Reparation and Non-Repetition (SIVJRNR) which was established as a result of the peace agreement between the government and the FARC, COSPACC and its allies have presented several reports to the Truth Commission (CEV) and the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP).

Among the documented cases are those of the forced disappearance of civilians in the Corporation’s work regions. Beyond documenting cases, COSPACC has set itself the task of uncovering the dynamics of the conflict in the departments of Guaviare and Boyacá, and helping with locating mass graves where the remains of victims of this scourge are allegedly buried. This work is carried out in a coordinated effort with the Unit for the Search for Missing Persons (UBPD).16

According to the Popular Research and Education Centre (CINEP), an allied organization in this project, despite the fact that in the municipality of Puerto Boyacá the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) were founded, Boyacá is one of the departments where the violence committed during the armed conflict has been consistently covered up: “Little is known about the massacres that the paramilitaries carried out there, or about the many victims of the social and political conflict,” according to this research centre.17 In an effort carried out in close relationship with the local communities and the families of the disappeared, COSPACC and CINEP want to uncover the horrors experienced by the population at the hands of the paramilitary groups that operated there.

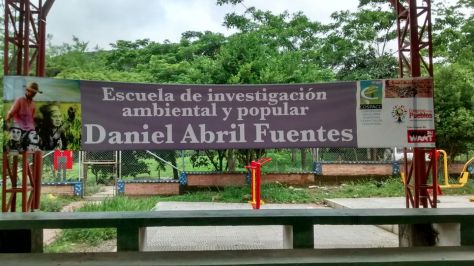

The ‘Daniel Abril Fuentes’ School of Environmental and Community Research

The killing in November 2015 of Daniel Abril Fuentes, environmental defender and partner of the COSPACC regional team in Casanare, was in the words of Fabian Laverde, “an event that marked our lives, both professionally and personally.”18

Through different alliances and platforms Abril promoted the memory of the victims of state crimes and human rights violations and organised actions “that disturbed the interests of powerful businesses who sought to control our territories for mining.”19 He had already suffered threats, attacks, false accusations and arrests, when he was assassinated in his hometown Trinidad in Casanare.

The Daniel Abril Fuentes School of Environmental and Popular Research was created in his memory. It carries out organizational strengthening and continues his work. The school offers a space for meetings and capacity building of community leaders and for rural and urban grass roots organizations in the region, especially those who have fallen victim to the human rights impacts of extractives industries and to state crimes. Supported by the school these organisations fight to protect their natural resources, food sovereignty and their local forms of production.

The U’wa indigenous reserve: a milestone in organisational strengthening

Some of the organisations COSPACC helps to strengthen are indigenous communities. It also raises awareness at national and international levels about the critical social and human rights situation of Colombia’s indigenous peoples. An important achievement was the accompaniment of the U’wa community of the Chaparral Barronegro reserve in their organisational processes and defence of their territory against large-scale economic projects in the region.

The reserve, created in 1986, is situated in the north of Casanare. it has a population of approximately 500 inhabitants and an area of 16,824 hectares.

According to COSPACC, one of the milestones of their work here has been halting the militarization of the reserve by the National Army and Air Force, as well as resisting the entry of oil companies in the territory.20 COSPACC’s efforts were carried out in a coordinated effort with the Indigenous Regional Organisation of Casanare (ORIC).

State pardon for family members of extrajudicial executions

In 2016, COSPACC and allied organizations such as CSPP achieved that for the first time in the country’s history, a high-ranking Army officer had to answer in a trial for his alleged responsibility in several cases of extrajudicial executions. General (r) Henry William Torres Escalante, who according to the Office of the Attorney General of the Nation allegedly had been the intellectual author of the murder of Daniel Torres Arciniégas and his 16-year-old son Roque Julio Torres.21 The two peasants, who were grassroots members of COSPACC in the municipality of Aguazul, were presented by the 16th Brigade under the command of Torres Escalante, as ELN guerrilla militias killed in combat.

In August 2019, Bogotá’s administrative court no. 61 ordered the Ministry of Defence and the National Army to stage an act of public forgiveness to the relatives of father and son Torres for these extrajudicial executions. At that time, the Torres Escalante case was left to the JEP, since the former commander of the 16th Brigade had expressed his decision to submit to transitional justice.22

Although the retired military officer went to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) to publicly present his excuses and ask the victims for forgiveness, he did so while not accepting his responsibility for what happened. Torres Escalante assured that when he was commander of the 16th Brigade his subordinates hid the “false positives” from him. In a public statement in November 2019, the victims of the crimes insisted that it was an insult to the memory of family members and other citizens. Arguing that they are not willing to lend themselves to ridicule or revictimization, the victims refused to attend the voluntary versions scheduled for the case at the JEP.23

Threats and attacks

Since its beginnings the members of COSPACC have suffered persecution, threats, robberies and arrests, for which they have filed several criminal complaints against the Public Force in Casanare for abuse of authority, arbitrary detention and theft of information.24

Shortly after the establishment of the organization, in 2003, its founder, Francisco Cortes Aguilar, was imprisoned and held in Bolivia, accused of rebellion.25 He was released two years later after an intense campaign in which United Nations (UN) called the arrest arbitrary26, and in 2014 he was found dead in strange circumstances. The murder of Daniel Abril in 2015 shows that even in recent times where paramilitary terror and associated violence no longer dominate the scene, COSPACC members continue to be at great risk.

The investigations carried out by COSPACC into environmental harm and human rights violations in the operating areas of some multinationals, have generated tensions and opposition on the part of companies and public entities directed against the organization. The fact that COSPACC and its allies work on high-profile cases, among them the process against former Army general Torres Escalante, increases their risks. During 2019 and during the first half of 2020, they have suffered smear campaigns, have been illegally followed and have fallen victim to other security incidents, which sometimes involve Police and Army members.27

“If I was prepared to die I wouldn’t be working as a human rights defender”: Fabián Laverde

Protection measures

From 2006 to 2010 COSPACC had temporary protection measures in place assigned by the Interior Ministry, which consisted of a communication device. When the National Protection Unit (UNP) was created the organization decided to renounce the measures for fear of interceptions. Their fears had to do with the background of UNP officials, who had been part of the former Administrative Security Department (DAS), infamous for scandals around illegal interceptions and other secret intelligence activities against human rights defenders.28

In 2019, a collective request for Precautionary Measures was presented to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in 2018 by the National Movement of State Victims (MOVICE) and other human rights organizations, and which included COSPACC among its beneficiaries. The request was rejected by the IACHR.

Awards and recognition

In 2014 COSPACC was a finalist for the Franco-German Antonio Nariño Human Rights Prize and the following year, the organisation received the National Prize for the Defence of Human Rights Diakonia in Colombia in the category “Collective experience or process of the year, NGO level”.29

PBI accompaniment

We have been accompanying COSPACC since 2009.

Contact

Social media

- Twitter: @COSPACCOficial

Footnotes

1 COSPACC: Persecución a la Asociación Departamental de Usuarios Campesinos de Casanare –ADUC-, 2019; Movice: Capítulo Casanare en contexto, 18 January 2018

2 The National Prize for the Human Rights Defense Diakonia: COSPACC, 1 Octobre 2015

3 Rutas del conflicto: Casanare: a la sombra de los desaparecidos, consulte don June 2020

4 PBI Colombia: interview with Fabian Laverde, COSPACC president, 18 December 2019; and 20 December 2019

5 Op.cit. Interview with Fabian Laverde, 18 y 20 December 2019

6 PBI Colombia: Interview with a Fabián Laverde, 11 August 2016

7 Op.cit. Interview with Fabian Laverde, 18 y 20 December 2019; Business & Human Rights ressources Center: BP lawsuit (re Casanare, Colombia, filed in the UK), 9 November 2014; War on Want: “Report: Bad Company – BP, human rights and corporate crimes”, 24 June 2017

8 El Espectador: Iván Cepeda denuncia convenios entre empresas mineras y batallones militares, 3 November 2015

9 Op.cit. Interview with Fabian Laverde, 18 y 20 December 2019

10 Resumen Latinoamericano: Asentamientos humanos por necesidad, 11 February 2020

11 El Espectador: En Colombia 202 defensores del ambiente han sido judicializados: informe ante la CIDH, 28 September 2019; OMCT: Colombia: [Nuevo informe] Crónica de una judicialización anunciada – La defensa de derechos humanos, al banquillo de los acusados, 12 December 2019

12 Op.cit. Interview with Fabian Laverde, 18 y 20 December 2019

13 Ibid

14 El Espectador: “Los convenios del Ministerio de Defensa en un caso contra líderes sociales en Casanare”, 15 September 2019

15 CSPP, Cospacc, OMCT: “Criminalización de la defensa de los derechos humanos en Colombia: la judicialización a defensores/as de la tierra, el territorio, el medio ambiente y la paz”, 11 December 2019

16 Op.cit. Interview with Fabian Laverde, 18 y 20 December 2019

17 Trochando sin Fronteras: Hilar voces, tejer memorias, la propuesta de las víctimas en Lengupá, 5 April 2019

18 J&P: Daniel Abril Fuentes, 13 November 2019

19 Ibid

20 PBI Colombia: Interview with Fabián Laverde, September 2015

21 CSPP: Pedirán traslado del general Escalante a cárcel del Inpec, 5 April 2016

22 El Espectador: Condenan al Estado por caso emblemático de falsos positivos, 25 de agosto de 2019

23 El Espectador: Víctimas se niegan a ir a la JEP en el caso del general (r) Torres Escalante, 11 de noviembre de 2019

24 PBI Colombia: Interview with Cospacc, August 2016

25 Ccajar: Hasta Pronto Compañero Francisco “Pacho” Cortés, 7 October 2014

26 United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions: Opinion No. 12/2005 (Bolivia), 2 February 2005

27 Op.cit. Interview with Fabian Laverde, 18 y 20 December 2019

28 El Espectador: Los escándalos del DAS, 31 January 2015

29 Premio Nacional a le Defensa de los Derechos Humanos Diakonia: Defensores derechos humanos visitan Washington, 15 February 2016

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.

Your web site provided us with valuable information to work

on. You’ve done a formidable job and our entire community will be thankful to you.

Having read this I believed it was extremely enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort to put this informative article together.

I once again find myself personally spending a significant

amount of time both reading and leaving comments. But so what,

it was still worth it!

I drop a leave a response whenever I like a post on a website or if I have something to valuable to contribute to the conversation.

Usually it’s caused by the passion communicated in the article I looked at.

And after this post COS-PACC | PBI Colombia. I was actually excited enough

to drop a comment 😉 I actually do have 2 questions for you if

you usually do not mind. Is it simply me or does it

look like like some of these remarks come

across like written by brain dead folks? 😛 And, if you are posting on additional social sites,

I’d like to keep up with you. Could you make a list the complete urls of your

shared pages like your Facebook page, twitter feed, or linkedin profile?